Role of Faith in a Secular World

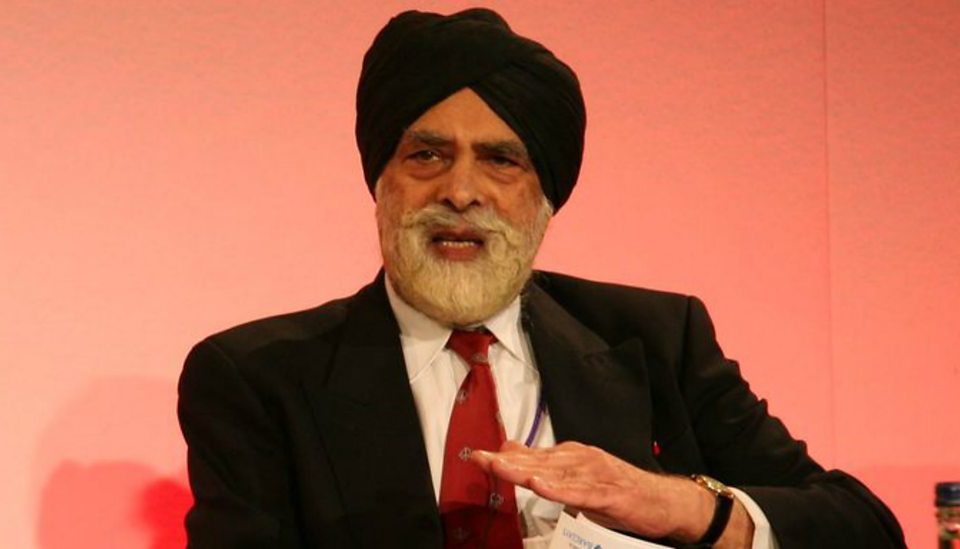

Lord Indarjit at the Parliament of Religions, 2015

November 10, 2015Role of Faith in a Secular World, Lord Inderjit Singh of Wimbledon @The Parliament of Religions, 2015, Salt Lake City

Lord Indarjit Singh of Wimbledon

Friends, it is a real pleasure to be invited to talk to you on a key subject for all different faiths: The Role of Faith in a Secular World.

Today, we look with bewilderment and disbelief at brutalities inflicted on the suffering people in Syria, Iraq and much of the Middle East and in many other parts of the world. Killing in the name of religion is nothing new. Guru Nanak, the founder of the Sikh faith was himself a witness to the Mughal invasion of India and the atrocities against a mostly Hindu population. The Guru, reflecting on the killings and atrocities, put the blame firmly on the divisive packaging of competing faiths, as superior and exclusive paths to God, with claims to be inheritors of God’s patronage and ‘final revelation’.

It’s this bigotry of belief with God on our side, applauding all we do in his name, that led to conflict in the past and today, is used to justify killings and atrocities against thousands of innocents across the world.

Guru Nanak, in teachings rooted in compassion and common sense, argued that the one God of all humanity does not have favourites and is not in the least bit interested in our different religious labels but in what we do. He saw different religions as different paths to responsible living, and taught that all such paths should be respected.

Guru Arjan the fifth of Guru Nanak’s nine successor Gurus, emphased this need for respect between different faiths by asked a Muslim saint Mia Mir to lay the foundation stone of the Golden Temple to show his respect for Islam, In the world’s first major move in inter faith dialogue, he included verses of Hindu and Muslim saints in our holy scriptures, the Guru Granth Sahib, to underline the central Sikh teaching that no one religion has a monopoly of truth; a concept, that in my view , is essential if our different faiths are to play their true role of giving meaning and direction to compassionate and responsible living.

It is important to remember that misplaced religious zeal is not the only cause of conflict in our troubled world. Stalin, Hitler and Pol Pot were not particularly religious. A few years back, I did some work for the Human Rights organisation Amnesty International, looking at genocide and human rights abuse in a number of different countries; abuse which often involved unbelievable depravity. Almost as bad as the abuse, was the realisation that those who we learn to trust are often the perpetrators: police and soldiers, and, even worse, priests and teachers and previously friendly neighbours. Why do people behave in such ways?

The sobering conclusion is that our human family has only a thin veneer of civilisation that differentiates us from those we call savages; a veneer that is all too easily shed at times when, either through misplaced religious zeal or the simple pursuit of power, we are persuaded to see others as lesser beings.

How can we move our wayward human race into what Sikhs would call a Gurmukh or Godly direction? Why has organised religion lost its sense of direction?

The problem, is that the ethical teachings of our different faiths, are extremely easy to state, but difficult to live by. It is hard to put others before self; it is hard to forgive. Lust and greed have their attractions. So, in our perverse, way we develop surrogates for true religious teachings. If, once a week, we sing words of ethical guidance in beautiful hymns and chants, perform rituals, build beautiful places of worship, fast, and go on pilgrimages, we can easily convince ourselves, that we are following the main thrust of religious teachings.

Guru Nanak, the founder of the Sikh faith was not too impressed with such practices. He taught:

Pilgrimages, austerities and ritual acts of giving or compassion

Are in themselves, not worth a grain of sesame seed

It’s living true to ethical imperatives that count. It’s much easier to look to the trappings of our different religions, than to their actual teachings. Sikhism, is a fairly new religion and we haven’t had much time to develop rituals to take the place of ethical imperatives. But sadly, we are doing our best to catch up, with interminable arguments over the holiness of sitting on the ground as opposed to chairs or buffet, in the meal that follows Sikh services, and in other ways that confuse peripheral arguments with true religion.

The vacuum created by this failure to focus on key religious teachings was quickly filled by the pursuit of material wealth. Society rightly rejected the so-called religious view that taught spiritual improvement and at the same time countenanced poverty, disease and suffering. Unfortunately, the pendulum has swung too far and mankind is engaged in seeking happiness and contentment through the blind pursuit of material wealth to the neglect of the spiritual side of life.

To me as a Sikh, much of the unhappiness in the world today stems from our basic failure to recognise that life has both spiritual and material dimensions, and if we neglect either of these, it will be to our ultimate neglect. This fundamental truth has, as you all know, long been recognised by our religious

founders.

Sikhism gives the story of the miser Dunni Chand who spent all his time amassing wealth until he was given a needle by Guru Nanak to take into the next world. On another occasion, the Guru gently chided some so–called holy men who had left their families to go in the wilderness in search of God. The Guru told them that God was not to be found in the wilderness but in their homes in looking to the needs of their families and others around them.

The Guru taught that we should live like the lotus flower, which having its roots in muddy waters, still flowers beautifully above. Similarly we should all live and world for the benefit of society, but should always be above it meanness and pettiness.

Today in our preoccupation with things material, we have forgotten the importance of balance between material and spiritual and, as a result, have previously unheard of prosperity side by side with escalating crime, rising alcoholism and drug dependency, loneliness, the homeless and broken homes and other disturbing evidence of social disintegration.

How can we move to more balanced and compassionate living? How can we make ours a more cohesive and caringsociety. Voluntary effort and increasingly government and other statutory effort are becoming more alert to social ills in our society. But in focussing on problems, rather than more holistically on causes, we sometime tend to look through the wrong end of the telescope, and seek to treat spots and sores of social maladies, rather than look further to underlying causes.

If problems resulting from drug abuse take up too much police time, the call is legalise drug use and free the police, rather than question why the use of drugs has risen so dramatically. ncreasing alcohol abuse? Let’s extend or abolish licensing hours to spread the incidence of drunken or loutish and drunken behaviour. Result, a rise in binge drinking. Too many people ending up in prison? Let’s build more prisons. Extend this thinking, of looking to the wrong end of a problem, to the behaviour of little junior who greets visitors to the house by kicking them in the shins. Solution: issue said visitors with shin pads as they enter the front door!

It is important to differentiate between two levels of behaviour. The first is behaviour that keeps us out of trouble. For the small child it not throwing food about, or not kicking aunts and uncles in the shins. For adults it’s being reasonably polite to those around us, and complying with those in authority and the rules and laws of society, unless we know we can get away with it!

Is religion necessary for promoting such conformity? Of course not. No more than it’s necessary to involve religion in teaching a dog to stand on its hind legs or a dolphin to perform tricks. Sanction or reward in the teaching of social norms are sufficient motivators. Hindsight however reminds us that accepted social norms of the day, like acceptance of slavery or discrimination on grounds of gender or ethnicity can later be seen cruel and oppressive.

The teachings of our great religious leaders on the other hand, frequently challenge social norms. Religious teachings have nothing to do with unthinking conformity, or, equally importantly, individual or material advancement. Instead, they look to spiritual and ethical advancement for both the individual and society as a whole.

Religion takes us away from obsession with self, to active concern for others. As Guru Nanak taught, where self exists there is no God, where God exists there is no self. Or as a Christian theologian put it‘ it’s the ‘I’ in the middle of ‘sin‘ that makes it Sin. Ironically, a recent edition of the Journal Experimental Psychology after detailed recent studies underlined the same important truth. Religion then, is fundamentally different from civics or citizenship education, in that far from conforming, it has its own standards that often can and do, challenge existing unjust and discriminatory social norms.

This is particularly important because politics and the democratic process are geared to pandering to short- term popularity, and this can result in populist policies that harm our long-term interests. In a debate in the British House of Lords, a speaker argued that ‘religion was out of step with society’. I replied that to me this was like saying, my satnav is not following my directions.

Sikhs believe that our different religions should work together and take the lead in addressing the real causes of our social ills – starting with the role of the family. We see marriage, fidelity and the family as central to the health and wellbeing of society. It is easy to allow understanding, compassion and support for those in different situations to blind us to the importance of an ideal. TV comedy in which infidelity is seen as something of a giggle, blinds us to the hurt that transient, adult relationships, can cause to children.

A short true story makes the point better than any words of mine.

Two small boys were fighting, hammer and tongs in the school playground. With great difficulty, a teacher finally managed to prise the two apart demanding to know what it was all about. Looking at the teacher, with eyes swollen with tears, one of the children said it was because the other’s dad had taken his mum away.

While we should not condemn those who chose different lifestyles, there is a need for clearer highlighting of responsibility and the benefits of stable family relations. Both those in political life and leaders of faith communities have much to do here.

Today, in our yearning for peace we know the direction in which we have to go. Yet, rooted in material greed, bigotry and selfishness, we continue in a direction that is bound to lead to further conflict. We talk of a common brotherhood yet are prepared to accept our brothers and sisters and their children being killed by bullets and bombs manufactured by us and other developed and developing countries. Even India, the land of Mahatma Gandhi, boasts that it is now a major exporter of arms

Most industrialised nations see the arms industry as an important earner of foreign exchange as well as a means to political leverage on the less ‘developed‘ world, often regardless of gross human rights abuses in recipient countries. The current situation in the Middle East is a case in point. We criticise Russia for supporting President Assad, a dictator without a democratic mandate. Yet, in the name of strategic interest, the West sells billions of dollars of arms to Saudi Arabia, a country that ferments unrest in the region, a country that barbarically beheads hundreds of those who dissent from its dictatorial rule every year, and amputates the limbs of many others. A country that oppresses women and does not allow Sikhs and other faiths to openly practice their religion. Yet, with Britain’s help, Saudi Arabia today chairs the UN Human Rights Council.

Unbelievably, when I questioned, in the House of Lords, the morality of a government statement that human rights should not be allowed to get in the way of trade with China, I received a reply to the effect that strategic interest must trump human rights!

When a government Minister spoke of the need for an international inquiry into human rights abuse in Sri Lanka, I congratulated the government, and asked if they would support a similar inquiry into the widespread killing of Sikhs in India in 1984, I received a short, sharp reply:’ that is a matter for the Indian government!-a much bigger trading partner. It was the great Human Rights activist, Andrei Sakharov who wisely reminded us that ‘there will never be peace in the world until we are even handed in human rights abuse.

As our children and grandchildren look back on today’s times, I am sure that they will do so with loathing and revulsion at a generation prepared to countenance and continue the suffering of millions for its own economic prosperity. Today, the dominant creed in much of the world is that individual happiness and so-called strategic interest are all that really matter What do we need to do to change to promote greater social justice both at home and abroad?

In ‘do it yourself’ activity, there is a saying that when all else fails, look at the instructions. In the past, religion failed to give true ethical direction because it looked more at the packaging than on far seeing guidance. Arrogant secular society isn’t, as we’ve seen, doing much better and it is the responsibility of our different religion to get it to look and act on the ethical instructions for sane peaceful and responsible living contained in the teachings of our different faiths

The first step in doing this is to move from hostility and suspicion of one another, to true respect and tolerance. Not the sort of tolerance that grudgingly puts up with others, but a tolerance that says, in the words of Voltaire, ‘I may not believe in what you say, but will defend to the death your right to say it’. A sentiment translated into action by Guru Teg Bahadhur, the 9th Guru of the Sikhs, who was martyred defending the right to freedom of worship of the Hindu community, against Mughal persecution.

The second step would be drastic spring-cleaning of religion. Today there is an urgent need for us to discard rituals, superstitions and dated customs and practices that have nothing to do with teachings of the founders of our different. Practices that here over years become falsely attached to religion and simply serve to distort teachings. Practices and customs that have no relevance to life today. We need to look at guidance in the context of today’s times rather than the particular social or political circumstances of earlier days.

At the same time, we have to knock down the false barriers of belief and exclusivity between religions. When, in the course of redevelopment, a building is demolished in a familiar area, we see the surrounding landscape in a quite different light. In the same way, when false barriers of bigotry are demolished through dialogue and understanding, we will see our different religions as they really are: overlapping circles of belief, in which the area of overlap is much greater than the smaller area of difference In that area of overlap, we find common values of tolerance, compassion and concern for social justice: values that can take us from the troubled times of today, to a fairer and more peaceful world.